Peter Phillips: British Pop Art Icon and Cultural Provocateur Dies Aged 86

Peter Phillips, one of the central figures in the British Pop Art movement, has died at the age of 86. His passing was confirmed by family on June 23, at his home on Australia’s Sunshine Coast, where he had been living since 2015. No cause of death was disclosed.

A pioneer and provocateur, Phillips emerged in the 1960s as a disruptive force in a postwar Britain still shedding the greys of austerity.

Born in Bournville, Birmingham, in 1939, his upbringing in an industrial working-class family deeply influenced his art, art that was unapologetically loud, brash, and bursting with the glitter of consumerist iconography.

“When I was young, the only way to make a living as an English artist was to either teach or to secure the patronage of a wealthy aristocrat,” Phillips once remarked in a candid interview with Orlebar Brown.

“But London in the late ’50s was changing, and a small group of us started to use popular images for our pictures, which was frowned upon at the time. We never called it ‘Pop Art’; we were just trying to express who we were.”

At the Royal College of Art, Phillips absorbed the boldness of American artists like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. He didn’t just observe, he applied.

By 1961, he was among the breakout names in the “Young Contemporaries” exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, exhibiting alongside future art titans like David Hockney and R.B. Kitaj.

Often dubbed the “tough guy” of British Pop, Phillips favoured a muscular style. His work mashed together Hollywood glam, pinups, motoring dreams, and symbols of pop consumer culture.

His standout piece, For Men Only, Starring MM and BB, fused Marilyn Monroe, Brigitte Bardot, lingerie ads, and snippets of Melody Maker. It was provocative. It was cheeky. It was bold.

He didn’t stop at galleries. Phillips’ flair for merging art with mass appeal made its way onto record sleeves. His 1972 painting Art-O-Matic Loop Di Loop became the iconic cover of The Cars’ 1984 album Heartbeat City. The Strokes followed suit in 2003, using a portion of their work War/Game for Room on Fire.

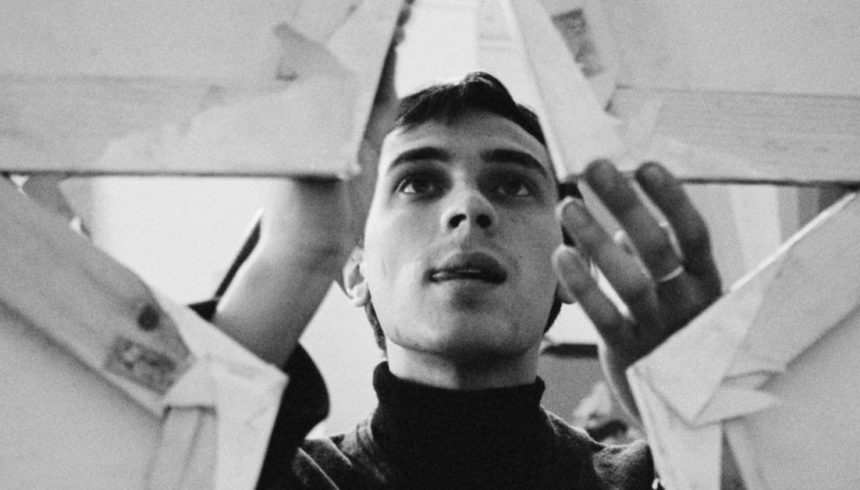

His charisma wasn’t confined to the canvas either. In Ken Russell’s 1962 BBC documentary Pop Goes the Easel, Phillips glides through his West London studio in a turtleneck, as a woman plays pinball beside his mixed-media artwork The Entertainment Machine, a vivid tableau of bullets, piano keys, and targets.

“I believe in living in the times you are born into,” he told The Birmingham Post in 1963. “I don’t think a painter should isolate himself from the world he is living in — I can’t, anyway.” He added, “Ours is a consumer society. That interests me.”

Though Phillips was born as bombs fell over Birmingham during WWII, he leaned toward celebrating life’s excesses.

“So many other people went through it, too,” he later said in Art + Australia. “So that as so-called Pop artists, we were on to a lighter subject.”

After his foundational years at Birmingham College of Art and the Royal College, Phillips rose to international acclaim. He featured at the 1963 Paris Biennale and the famed “Nieuwe Realisten” exhibition in The Hague in 1964.

He wasn’t just part of the Pop Art revolution. He was its core. And he carried it from the gritty streets of Birmingham to global recognition.

Peter Phillips is remembered not just for what he painted, but for the way he challenged the very idea of what art could be. Bold. Daring. Unapologetically modern.