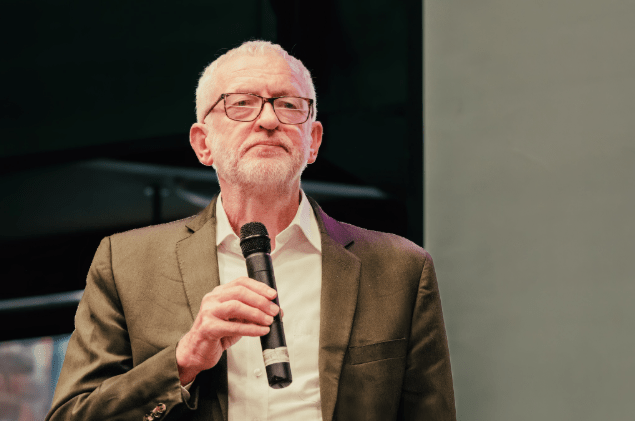

Jeremy Corbyn’s latest political project may have had a bumpy start, but it is already sending ripples through Westminster.

The veteran MP for Islington North has vowed to “build a democratic movement that can take on the rich and powerful” – a bold pledge forming the heart of his “new kind of political party”.

The as-yet-unnamed movement is gearing up for the next general election, and, intriguingly, could feature a roster of familiar faces from Labour’s own benches.

Sources close to the new party say it is actively courting former allies from Corbyn’s Labour years, hoping to capitalise on the party’s current struggles in the polls.

The strategy is clear: tempt MPs disillusioned with Sir Keir Starmer’s leadership by presenting a stark choice – stay with Labour and risk losing your seat, or join a fresh movement with a promise of survival.

Although no names have been confirmed, the Socialist Campaign Group, which counts ex-shadow minister Ian Lavery and MP Ian Byrne among its members, is said to be on the radar.

The recent uproar over Labour’s proposed welfare cuts – opposed by more than 120 Labour MPs – has provided fertile ground for recruitment. Liverpool, where MP Kim Johnson led resistance, has reportedly shown strong grassroots support for Corbyn’s cause.

Senior Labour ministers may also find themselves in the crosshairs. Figures such as Health Secretary Wes Streeting and Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood saw their majorities dented by pro-Gaza challengers last year – a vulnerability Corbyn’s party may seek to exploit.

Early polling shows potential headaches for Labour. A Find Out Now survey placed the new party level with Labour at 15% each, with Reform UK surging at 34% and the Conservatives trailing on 17%. Pollster Luke Tryl noted that a Corbyn-led force “took 10 per cent of the vote, taking votes from Labour and the Greens”.

Political veteran Sir John Curtice told The Independent that “Labour are vulnerable to the left”, but warned, “At the moment, I’m waiting to see whether Corbyn manages to get his act together and manages to create a political party that has some thoughts and organisation behind it.”

If polling hints at promise, public engagement confirms it. Corbyn says more than 600,000 people have already signed up as supporters, many clustered in northern cities like Liverpool. A founding conference is planned later this year, preceded by regional meetings to harness local momentum.

Yet, insiders are wary. The threat of ‘entryism’ – infiltration by groups aiming to steer the party off course – looms large. This fear includes not only the far-right but also far-left factions such as the Socialist Workers, whose dominance could narrow the party’s broader appeal.

Membership pricing is also a sensitive topic. Set it too low, and it could attract those seeking to disrupt internal democracy, even pushing through a deliberately absurd party name.

The launch was met with a mix of excitement and mockery when a website called Your Party appeared, sparking speculation – swiftly dismissed by potential co-leader Zarah Sultana. Suggestions on the table range from ‘The Left’ to ‘The People’s Party’, though the latter’s European political associations may deter adoption.

Whatever the eventual branding, the impact at the ballot box will hinge on how many MPs Corbyn can lure away from Labour. If enough defects, Starmer’s path to Downing Street could become far rockier.