UK Inflation Spike Sparks Rate Cut Debate as BoE Caught in Balancing Act

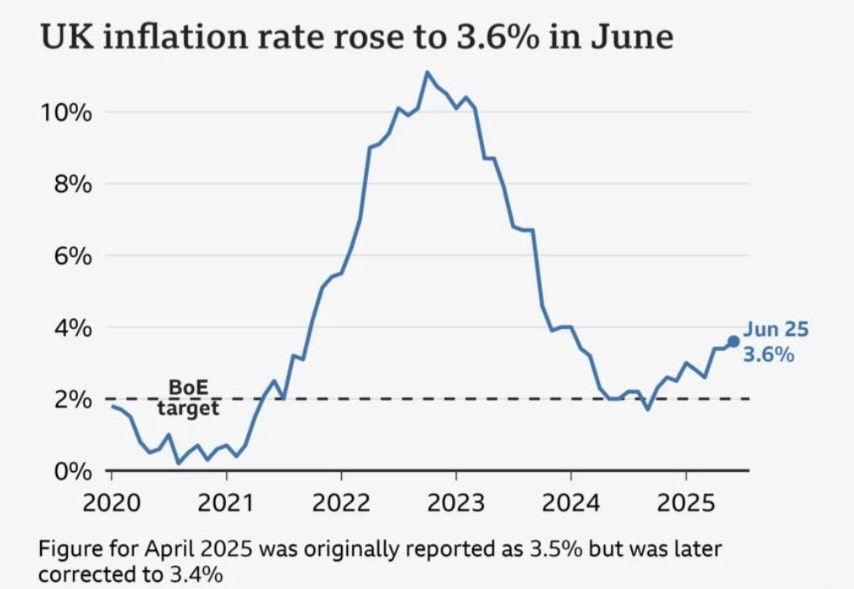

UK inflation has surged to its highest level since January 2024, rekindling debate around the Bank of England’s pace of interest rate cuts and raising fresh concerns over the cost-of-living outlook.

Data released Wednesday by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) revealed a surprise jump in the annual Consumer Price Index (CPI), hitting 3.6% in June—up from 3.4% in May. Economists had largely expected no change. This marks the sharpest rate of inflation in over a year.

It’s an uncomfortable turn for policymakers. Inflation had been slowing since peaking in 2022, but that decline is now losing momentum. Since last autumn’s low of 1.7%, the trend has reversed.

The Bank of England (BoE) had forecast inflation would climb to 3.7% by September. We’re nearly there—and earlier than expected.

Sterling edged up slightly after the news. Gilt yields also rose, and markets trimmed expectations of a summer rate cut.

Still, not everyone is convinced that the BoE will slam on the brakes. “There’s enough of a slowdown in GDP and the labour market to warrant a ‘gradual and careful’ easing of monetary policy.

But the onus now rests on the labour market to shape how far and how fast the MPC can cut this year and next,” said Sanjay Raja, Deutsche Bank’s Chief UK Economist.

ONS pointed to rising prices across fuel, transport, air travel, food and drink. Train fares and clothing costs also crept higher. Food and non-alcoholic beverages were up 4.5% year-on-year—the sharpest increase since February.

Alcohol wasn’t spared either. A hike in prices for red wine and lager added to the squeeze.

Inflation has also been pushed higher by earlier price surges in regulated energy, water, and employment taxes—especially in April when CPI jumped from 2.6% to 3.5%.

Rachel Reeves, the UK’s new finance minister, acknowledged the pressure on households. She pointed to government measures aimed at easing the burden.

The initiatives include a higher minimum wage, free breakfasts for young children, and fare caps on buses. Yet with inflation proving more stubborn than hoped, such measures might only cushion the blow rather than solve the underlying issue.

The Bank of England has already made four quarter-point cuts since last August. Two more were widely expected this year, including one potentially in August.

But sticky inflation, especially in the services sector—where price growth held at 4.7%—has muddied the outlook. “The risk is that this increase proves more persistent and rates are cut more slowly than we expect, or not as far,” warned Ruth Gregory, deputy chief UK economist at Capital Economics.

Economic growth isn’t offering much comfort either. GDP figures released last week showed a surprise contraction in May. Wage growth remains hot too, with new data expected Thursday.

Still, BoE Governor Andrew Bailey remains cautiously optimistic. He sees rates heading lower—though slowly—as a softer labour market tames pay pressures.

The Bank’s long-term vision remains firm. Inflation, it believes, will return to the 2% target by early 2027. “The fall in inflation is likely to be gradual, reflecting ongoing stickiness in the services category,” added Matt Swannell, chief adviser at EY ITEM Club.

UK inflation may not be out of control, but it’s proving annoyingly stubborn. And while rate cuts are still on the table, the timeline is now under serious scrutiny.

For households, it’s a waiting game. For the BoE, it’s a balancing act between taming inflation and not choking off growth. One thing’s clear: UK inflation is once again at the heart of the country’s economic story.